For me, ‘yoga’ means wholeness.

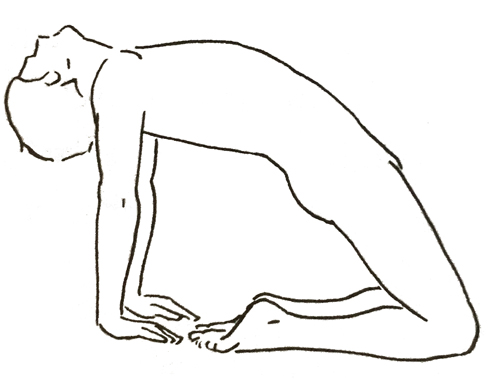

My understanding of yoga is extremely wide. At this extreme, it has to do with almost nothing. I do, however, love practicing modern yoga at the studios…

‘lokah samastah sukhino bhavantu.’ Peace. Om.

Tips from friends:

‘Going beyond’ is not to be considered as any kind of transcendence in the traditional sense. The whole import of Dōgen’s key term ‘dropping off’ is diametrically opposed to ‘climbing over’ (trans-cendere) and refreshingly obviates meta-physics, trans-metaphysics, meta-meta-meta-physics and the whole business of ‘meta’ of which it is fervently hoped we have truly had our philosophical fill.

–Joan Stambaugh, The Formless Self (1999)

For example, a personally based mode of inquiry reflecting his own mystical experiences and interest in psychoanalysis animates [Romain Rolland’s] depiction of Yoga. Yoga, he correctly related, was derived from the same Sanskrit root as the English ‘yoke,’ which meant ‘to join,’ and implied union with the divine. However, the purpose of Yoga consisted in far more than the inducement of mystical feelings of unity. Yoga was a ‘science of the soul,’ a psychophysiological method that was experimentally and scientifically verifiable. Yoga adopted the introspective-empathic mode of observation with the aim of coming to ‘know the laws that govern the passions, the feelings, the will of mankind.’ Yogic techniques enabled the ego to gain access to and hence mastery of unconscious contents. Its goal, like that of psychoanalysis, was freedom. The characteristic of mystical introversion was not weakness and ‘flight’ – that is, the employment of any number of defense mechanisms against repressed contents, as many in the West had taken it to be, but strength and combat. ‘The ancient Yogi’s,’ states Rolland, ‘did not wait for Dr. Freud to teach them the best cure for the mind is to make it look its deeply hidden monsters straight in the face.’ Strength and the will to arrive were essential to undertake the rigors of Yogic training. The practical results of this psychic surgery were insight, renunciation of instinct, freedom from the return of the repressed, and a strengthening of individuality. Yoga was also seen as conducive to the generation of creativity–great artists had ‘instinctively’ and ‘subconsciously’ practiced it.

– William B. Parsons, The Oceanic Feeling Revisited (1998)

The practice of respiration, the practice of diverse kinds of breathing certainly reduces the darkness or the shadows of Western consciousness. But above all it constitutes the mental in a different way. It grants more attention to the education of the body, of the senses. It reverses in a way the essential and the superfluous. We Westerners believe that the essential part of culture resides in words, in texts, or perhaps in works of art, and that physical exercise should help us to dedicate ourselves to this essential.

The practice of respiration, the practice of diverse kinds of breathing certainly reduces the darkness or the shadows of Western consciousness. But above all it constitutes the mental in a different way. It grants more attention to the education of the body, of the senses. It reverses in a way the essential and the superfluous. We Westerners believe that the essential part of culture resides in words, in texts, or perhaps in works of art, and that physical exercise should help us to dedicate ourselves to this essential.

For the masters of the East, the body itself can become spirit through the cultivation of breathing. Without doubt, at the origin of our tradition—for Aristotle, for example, and still more for Empedocles—the soul still seems related to the breath, to air. But the link between the two was then forgotten, particularly in philosophy. The soul, or what takes its place, has become the effect of conceptualizations and of representations and not the result of a practice of breathing. The misunderstandings are so profound, proportional to historical forgetting and repressions, that bridges between the traditions are difficult to restore.

An Eastern culture often corresponds to becoming cultivated, to becoming spiritual through the practice of breathing. In this becoming the body is not separated off from the mental, nor is consciousness the domination of nature by a clever know-how. It is a progressive awakening for the entire being through the channeling of breath from centers of elemental vitality to more spiritual centers: of the heart, of speech, of thought. This requires time! Often an entire lifetime, a time that must remain in harmony with the rhythm of life in general, that of the universe and that of other living beings, which the candidate to the spiritual must respect, and even try to aid if such is their wish.

Spiritual progress is therefore not separated off from the body nor from desire, but these are gradually educated to renounce what harms them. To be sure, it is not a matter of renouncing for the sake of renouncing, but of renouncing what impedes access to bliss in this life. Asceticism is not therefore privative as it has too often been in the West. It is a limitation, accepted and willed, in order to progress toward happiness.

Such is the case with sexuality for example. Chastity is not presented as a good in itself, and the candidate for monasticism is often invited to first prove himself on the sexual plane. The gods of India, moreover, generally appear as a couple: man and woman creating the universe through their familiarity with certain elements, through their love as well, and they destroy it through their passion.

[…]On this subject it is important to meditate on the fact that a spirituality or a religion centered on speech, without insistence on breathing and the silence that makes it possible, risks supporting a nonrespect for life.

[…]In patriarchal traditions individual and collective life both wants to and believes it is able to organize itself outside of the surroundings of the natural world. The body—also called microcosm—is then cut off from the universe—which is called macrocosm. It is submitted to sociological rules, to rhythms foreign to its sensibility, to its living perceptions: day and night, seasons, vegetal growth . . . This means that acts of participation in light, sounds or music, odors, touch, or even in natural tastes are no longer cultivated as human qualities. The body is no longer educated to develop its perceptions spiritually, but to detach itself from the sensible for a more abstract, more speculative, more sociological culture. Yoga taught me to return to the cultivation of sensible perception. In fact, I have always loved it. Since my childhood, nature has helped me and has taught me how to live. But yoga brought me back to this taste with texts that lead me from the innocence of sensations to a spiritual elaboration that permits their development, and sometimes their communication or sharing.

[…]According to me, to learn, in the best of cases, is to learn from someone’s experience.To teach is to transmit an experience. What is taught is guaranteed by the life of the one who teaches, and by that of his or her own masters. In this way a concrete and spiritual knowledge is elaborated, a knowledge useful for a cultivation of life, for which the life of the teacher himself remains the support of truth, of ethics, and even of aesthetics. This practice of teaching constitutes a genealogy that is at the same time natural and cultural. In certain families knowledge is handed down from father to son, from mother to daughter, from father to daughter, from mother to son. In other cultural lineages the transmission occurs outside the natural family, from master to disciple. But, remaining linked to experience, it engenders a sort of milieu that is at once natural, sensible, and spiritual where knowledge of the past circulates and where that of the present and the future is elaborated. Indeed, a culture tied to experience cannot be reduced to the repetition of an already written corpus. Such a culture evolves, be it only according to the evolution of the universe, but also in the way of thinking the link between cosmic history and the history of living beings, particularly human beings, of this world.

[…]But why could love not come about in the respect and cultivation of my/our bodies? It seems to me that this dimension of human development is indispensable. Through scorn or forgetting of the body, what remains of it in our traditions is often reduced to elementary needs or to a sexuality worse than animal. To restrict carnal love to a reproductive duty, preceded by elementary coitus, at best by some vague caresses—when the man is not too overwhelmed with work, when one has the time—seems to me, in fact, a degeneration worse than bestial. The majority of animals have erotic displays that we no longer even have. Humiliation— especially of the woman—violence, guilt . . . are the lot of most couples in our supposedly evolved civilizations. This is something to be ashamed of! Because this means that love, for us and between us, has become less than human, except for some generous yet rare and often limited exceptions.

– Luce Irigaray, Between East and West (1999) (Translated by Stephen Pluháček)

I am much more interested in a question on which the ‘salvation of humanity’ depends far more than on any theologians’ curio: the question of nutrition.

– Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo (1888) (Translated by Walter Kaufmann)

What we do.– What we do is never understood but always only praised or censured.

– Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, Book Three (1887) (Translated by Walter Kaufmann)

*Note: You may have heard some hippies talking about “non-judgment.”

On the contrary, the point is to realize that by virtue of what you always are, have been, and will be, there is no need whatsoever to defend yourself or prove yourself.

– Alan Watts, Introduction to The Secret Oral Teachings in Tibetan Buddhist Sects (Alexandra David-Neel) (1967)

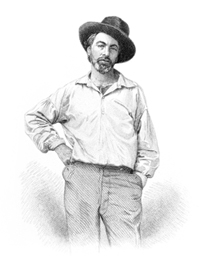

We shall speak by and by of health as being the foundation of all real manly beauty. Perhaps, too, it has more to do than is generally supposed, with the capacity of being agreeable as a companion, a social visitor, always welcome—and with the divine joys of friendship. In these particulars (and they surely include a good part of the best blessings of existence), there is that subtle virtue in a sound body, with all its functions perfect, which nothing else can make up for, and which will itself make up for many other deficiencies, as of education, refinement, and the like. We have even sometimes fancied that there was a wonderful medicinal effect in the mere personal presence of a man who was perfectly well! While, on the other hand, what can be more debilitating than to be continually surrounded by sickly people, and to have to do with them only?

We shall speak by and by of health as being the foundation of all real manly beauty. Perhaps, too, it has more to do than is generally supposed, with the capacity of being agreeable as a companion, a social visitor, always welcome—and with the divine joys of friendship. In these particulars (and they surely include a good part of the best blessings of existence), there is that subtle virtue in a sound body, with all its functions perfect, which nothing else can make up for, and which will itself make up for many other deficiencies, as of education, refinement, and the like. We have even sometimes fancied that there was a wonderful medicinal effect in the mere personal presence of a man who was perfectly well! While, on the other hand, what can be more debilitating than to be continually surrounded by sickly people, and to have to do with them only?

Do not be startled at the words, excellent reader. It is, in our view, indispensably necessary that a man should be a fine animal—sound and vigorous. This, to be candid with you, is the text and germ of most of our remarks—which arise out of it, and seek to promulge and explain how it can be fully accomplished.

[…]We, at the same time, know with the rest that a man has a moral, affectional, and mental nature which must also be developed; but we say that, at present, the whole tendency of things is to over-develope those parts, while the physical is cramped and dwindled away. Yes, reader, we teach that man must be perfect in his body first— we start with that as our premises, our foundation. We would throw into something like regular form a few principal hints and suggestions. Now this is to be done.

[…]With all this, we have an idea, amounting to profound conviction, that the highest and palmiest state of health, ministering to a long life, and accompanied throughout by all that makes a man physically the superior animal of the earth, and crowned at last with a painless and easy death—we have an idea, we say, that all this is only attainable, (except in rare natural instances,) by a cultivated mentality, by the intellectual, by the reasoning man. What else, indeed, is the whole system of training for physique, but intellect applied to the bettering of the form, the blood, the strength, the life, of man?

In other and shorter terms, true intellectual development, not overstrained and morbid, is highly favorable to long life, and a noble physique; and what falls short of these latter aims, (if attributable to anything in the mentality of the subject,) is, that the mentality of that subject was in a vitiated condition, or, (as in these latter days is often the case,) that there was not enough brute animal in the man. We repeat it, strange as it may seem, this is generally the case in these extra-mental and extra-philanthropic days of ours. That the half-way and unwholesomely developed mentality of modern times, as seen in large classes of people, literary persons, many in the professions, in sedentary employments, &c., acts injuriously upon the health, and militates against the noble form, the springy gait, the ruddy cheek and lip, and the muscular leg and arm of man, we know, full well. But, without wishing to be severe, what, critically considered, is the amount of modern mentality, except a feverish, superficial and shallow dealing with words and shams? How many of these swarms of “intellectual people,” so-called, are anything but smatterers, needing yet to begin and educate themselves in nearly all real knowledge and wisdom?

[…]Whatever is done, however, ought to be in the open air; don’t be afraid of that—drink it in—it won’t hurt you—there is a curious virtue in it, to be found in nothing else.

[…]It is a singular fact that what might be supposed such a simple accomplishment as perfect and graceful walking, is very rare—is hardly ever seen in the streets of our cities. We have plenty of teachers of dancing—yet to walk well is more desirable than the finest dancing. Perhaps some of the teachers we allude to might take a hint from the foregoing paragraph. A great deal may be done by gymnastic exercises to increase the flexibility and muscular power of the legs. The ordinary exercise of bending forward and touching the toes with the tips of the fingers, keeping the knees straight meanwhile, is a very good one, and may be kept on with, in moderation at a time, for years and years.

[…]The voice can be cultivated, strengthened and made melodious, with an ease and certainty, and to degrees of which very few people have any notion. We do not know a better exercise, either for young or middle-aged men, than practicing (at first with moderation), in loudly reciting and declaiming in the open air, or in some large room. This should be systematic and daily; it strengthens and develops all the large organs, opens the chest, and not only gives decision and vigor to the utterance, in common life, and for all practical purposes, but has a most salutary effect on the throat, with its curious and exquisite machinery, hardening it all, and making it less liable to disease. It helps, indeed, the bodily system in many ways—gives a large inspiration and respiration, provokes the habit of electricity through the frame, plays upon the action of the stomach, and gives a dash and style to the personality of a man.

[…]The habit of rising early is not only of priceless value in itself, as a means toward, and concomitant of health, but is of equal importance from what the habit carries with it, apart from itself. In nature, there is no example of the bad practice of an animal, in full development of health and strength, in fine weather, lingering in its place of rest, nerveless and half dead, for hours and hours after the sun has risen.

[…]One great point we would again impress on you, reader, (we have before reverted to it,) is the fact that your own individual case doubtless has points and circumstances which more or less modify all the general laws, and perhaps call for special ones, for yourself. This is an important consideration in all theories and statements of wealth [sic].

[…]Not only the looks and movement, but the feelings, undergo a transformation. It may almost be said that sorrows and disappointments cease: there is no more borrowing trouble. With perfect health, (and regular agreeable occupation,) there are no low spirits, and cannot be. A man realizes the old myth of the poets; he is a god walking the earth. He not only feels new powers in himself—he sees new beauties everywhere. His faculties, his eyesight, his hearing, all acquire superior capacity to give him pleasure. Indeed, merely to move is a pleasure; the play of the limbs in motion is enough. To breathe, to eat and drink the simplest food, outvie the most costly of previous enjoyments. Many of those before hand [sic] gratifications, especially those of the palate, drink, spirits, fat grease [sic], coffee, strong spices, pepper, pastry, crust, mixtures, &c., are put aside voluntarily—become distasteful. The appetite is voracious enough, but it demands simple aliment. Those others were was vexations [sic] dreams—and now the awakening. How happily pass the days! A blithe carol bursts from the throat to greet the opening morn. The fresh air is inhaled—exercise spreads the chest—every sinew responds to the call upon it—the whole system seems to laugh with glee. The occupations of the forenoon pass swiftly and cheerfully along; the dinner is eaten with such zest as only perfect health can give—and the remaining hours still continue to furnish, as they arrive, new sources of filling themselves, and affording contentment. How sweet the evenings! The labors of the day over—whether on a farm, or in the factory, the workshop, the forge or furnace, the shipyard, or what not—then rest is realized indeed. For who else but such as they can realize it? It is a luxury almost worth being poor to enjoy. The healthy sleep—the breathing deep and regular—the unbroken and profound repose—the night as it passes soothing and renewing the whole frame. Yes, nature surely keeps her choicest blessings for the slumber of health—and nothing short of that can ever know what true sleep is.

– Walt Whitman, Manly Health and Training, With Off-Hand Hints Toward Their Conditions (1858) (Available in full here)

*Note: This document, recently unearthed by a graduate student perusing the catacombs of knowledge, must reveal that something like the “yogic” spirit is universal, for Whitman seems alone to have come up with this wholesome advice. (Yoga, as we have it, was unknown to him, though a certain New Englander, noticing Whitman’s elective affinity for the East, recommended some books.) We are inclined to style this event: “qualified revelation.” Against revelation, we’ve long since speculated that knowledge is synthesized “inside” the metaphysical subject, that is, in the mind of the individual, whose bifurcated faculties – loosely speaking: reason and sensation, the one active, the other passive – cognize the world on the basis of a highly suspicious egoic unity. (And let it be clearly observed that even the so-called “black box” – the mind as referred to in computational and neuro-scientific discourses – is beholden to this suspicious unity: evidenced by the typically metaphysical distinction between what is inside the box and what is outside.) Never mind that the journalistically authoritative “naturalistic” reductionism which passes for insight among philosophical careerists cannot tolerate the existence of such a subject! (The so-called “hard problem of consciousness.”) If our claim concerning “qualified yogic revelation” – what a slogan! – were to be met with a skepticism respectable in the 1700s – “What do you mean revelation? It was Whitman’s opinion!” – we would with the best intentions refer our interlocutor to that other question: “Where did Whitman come from?” And if necessary, the questioning would be referred back and back until the mind fell into its nothingness. The return to sanity first made possible by this abyssal adventure would mean becoming whole: that holism which knows on the basis of existential experience that fact and value cannot be separated and that there is more to truth than correspondence with the facts!

When the warrior has unwavering discipline, he takes joy in the journey and joy in working with others. Rejoicing takes place throughout the warrior’s life. Why are you always joyful? Because you have witnessed your basic goodness, because you have nothing to hang on to, because you have experienced that sense of renunciation we discussed earlier. Therefore, your mind and body are continually synchronized and always joyful. This joy is like music, which celebrates its own rhythm and melody. The celebration is continuous, in spite of the ups and downs of your personal life. That is what is meant by being continually joyful.

When the warrior has unwavering discipline, he takes joy in the journey and joy in working with others. Rejoicing takes place throughout the warrior’s life. Why are you always joyful? Because you have witnessed your basic goodness, because you have nothing to hang on to, because you have experienced that sense of renunciation we discussed earlier. Therefore, your mind and body are continually synchronized and always joyful. This joy is like music, which celebrates its own rhythm and melody. The celebration is continuous, in spite of the ups and downs of your personal life. That is what is meant by being continually joyful.

The principle of meditative awareness also gives you a good seat on this earth. When you take your seat on the earth properly, you do not need witnesses to confirm your validity. In a traditional story of the Buddha, when he attained enlightenment someone asked him, “How do we know you are enlightened?” He said, “Earth is my witness.” He touched the earth with his hand, which is known as the earth-touching mudra or gesture. That is the same concept as holding your seat in the saddle. You are completely grounded in reality. Someone may say, “How do I know you are not overreacting to the situations?” You can say simply, “My posture in the saddle speaks for itself.”

At this point, you begin to experience the fundamental notion of fearlessness. You are willing to be awake in whatever situation may present itself to you, and you feel that you can take command of your life altogether, because you are not on the side of either success or failure. Success and failure are your journey. Of course, you may still experience fear in the context of fearlessness. There may be times on your journey when you are so petrified that you vibrate in the saddle, from your teeth to your hands to your legs. You are hardly sitting on the horse–you are practically levitating with fear. But even that is regarded as an expression of fearlessness, if you have a fundamental connection with the earth of your basic goodness.

[…]Cheering up is not based on artificial willpower or creating an enemy and conquering him in order to make yourself feel more alive. Human beings have basic goodness, not next door, but in them already. When you look at yourself in the mirror you can appreciate what you see, without worrying about whether what you see is what should be. You can pick up on the possibilities of basic goodness and cheer yourself up, if you just relax with yourself. Getting out of bed, walking into the bathroom, taking a shower, eating breakfast–you can appreciate whatever you do, without always worrying whether it fits your discipline or your plan for the day. You can have that much trust in yourself, and that will allow you to practice discipline much more thoroughly than if you constantly worry and try to check back to see how you are doing.

– Chögyam Trungpa, Shambhala, The Sacred Path of the Warrior (1984)

Learning to see – habituating the eye to repose, to patience, to letting things come to it; learning to defer judgment, to investigate and comprehend the individual case in all its aspects. This is the first preliminary schooling in spirituality: not to react immediately to a stimulus, but to have the restraining, stock-taking instincts in one’s control. Learning to see, as I understand it, is almost what is called in unphilosophical language ‘strong will-power’: the essence of it is precisely not to ‘will’, the ability to defer decision. All unspirituality, all vulgarity, is due to the incapacity to resist a stimulus – one has to react, one obeys every impulse.

– Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols (1888) (Translated by R.J. Hollingdale)

*Note: This invites comparison with the yogic concept pratyahara.

And now and then one hears from the lips of a traveler strange tales, tales of mysterious performances, of formidable feats practised in the observance of strange ritual. The masters of the art have nearly always served a rigorous spiritual apprenticeship. Self-discipline is the clue to their prowess. The man of God, in short, seems to have it over the gladiator.

– Henry Miller, The World of Sex (1941)

The destruction of the onto-theological foundation entails the destruction of moral science: “Thus, if you ask a genuine man who acts out of his own ground: ‘Why are you doing what you do?,’ he will reply, if his answer is correct: ‘I do it because I do it!'” As a rose that flowers without why, man’s life is an unexplained blossoming out of his own core. “Those who, with their deeds, look after something, those who work for a why, are bondsmen and hirelings.”

–Reiner Schürmann, Heidegger and Meister Eckhart on Releasement (1973) (Eckhart sermons: DW I, 92, 3-6; DW II, 253, 4f)

Even the wise act according to their nature.

All beings follow their nature.

So what can suppression accomplish?

–Bhagavad Gītā (1993) (Translated by Michael von Brück; my translation from the German)

In the dust-wiping type of meditation (tso-ch’an, zazen) it is not easy to go further than the tranquilization of the mind; it is apt to stop short at the stage of quiet contemplation, which is designated by Hui-neng ‘the practice of keeping watch over purity’. At best it ends in ecstasy, self-absorption, a temporary suspension of consciousness. There is no ‘seeing’ in it, no knowing of itself, no active grasping of self-nature, no spontaneous functioning of it, no chen-hsing (‘Seeing into Nature’) whatever. The dust-wiping type is therefore the art of binding oneself with a constructed rope, an artificial construction which obstructs the way to emancipation. No wonder Hui-neng and his followers attacked the Purity school.

– Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, The Zen Doctrine of No-Mind (1949)

The thought: ‘I am the doer’ is the bite of a poisonous snake.

To know: ‘I do nothing’ is the wisdom of faith.

Be happy.

–Ashtavakra Gita (2005) (Translated by Bart Marshall)

I wish to speak to the despisers of the body. Let them not learn differently nor teach differently, but only bid farewell to their own bodies – and so become dumb.

‘I am body and soul’ – so speaks the child. And why should one not speak like children?

But the awakened, the enlightened man says: I am body entirely, and nothing beside; and soul is only a word for something in the body.

The body is a great intelligence, a multiplicity with one sense, a war and a peace, a herd and a herdsman.

Your little intelligence, my brother, which you call ‘spirit’, is also an instrument of your body, a little instrument and toy of your great intelligence.

You say ‘I’ and you are proud of this word. But greater than this – although you will not believe in it – is your body and its great intelligence, which does not say ‘I’ but performs ‘I’.

[…]

Behind your thoughts and feelings, my brother, stands a mighty commander, an unknown sage – he is called Self. He lives in your body, he is your body.

There is more reason in your body than in your best wisdom. And who knows for what purpose your body requires precisely your best wisdom?

Your Self laughs at your Ego and its proud leapings. ‘What are these leapings and flights of thought to me?’ it says to itself. ‘A by-way to my goal. I am the Ego’s leading-string and I prompt its conceptions.

[…]–Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, A Book for Everyone and No One (1883) (Translated by R.J. Hollingdale)

Everything leads to the belief that, at the present moment, a more accurate knowledge of Indian thought has become possible. India has entered the course of history, and, rightly or wrongly, Western consciousness tends to take a more serious view of the philosophies of peoples who hold a place in history. On the other hand, especially since the last generation of philosophers, Western consciousness is more and more inclined to define itself with reference to the problems of time and history. For over a century, the greater part of the scientific and philosophical effort of the West has been devoted to the factors that ‘condition’ the human being. It has been shown how and to what degree man is conditioned by his physiology, his heredity, his social milieu, the cultural ideology in which he shares, his unconscious –and above all by history, by his historical moment and his own personal history. This last discovery of Western thought–that man is essentially a temporal and historical being, that he is, and can only be, what history has made him–still dominates Western philosophy. Certain philosophical trends even conclude from it that the only worthy and valid task proposed to man is to assume this temporality and this historicity frankly and fully, for any other choice would be equivalent to an escape into the abstract and non-authentic and would be at the price of the sterility and death that inexorably punish any betrayal of history.

It does not fall to us to discuss these theses. We may, however, remark that the problems that today absorb the Western mind also prepare it for a better understanding of Indian spirituality. Indeed, they incite it to employ, for its own philosophical effort, the millennial experience of India. Let us explain. It is the human condition, and above all the temporality of the human being, that constitutes the object of the most recent Western philosophy. It is this temporality that makes all the other “conditionings” possible and that, in the last analysis, makes man a “conditioned being,” an indefinite and evanescent series of “conditions.” Now, this problem of the “conditioning” of man (and its corollary, rather neglected in the West, his “deconditioning”) constitutes the central problem of Indian thought. From the Upanishads onward, India has been seriously preoccupied with but one great problem – the structure of the human condition. (Hence, it has been said, and not without reason, that all Indian philosophy has been, and still is “existentialist.”)

[…]With a rigor unknown elsewhere, India has applied it self to analyzing the various conditions of the human being. We hasten to add that it has done so not in order to arrive at a precise and coherent explanation of man (as, for example, did nineteenth century Europe when it believed that it explained man by his hereditary and social conditioning), but in order to learn how far the conditioned zones of the human being extend and to see if anything else exists beyond these conditionings. Hence it is that, long before depth psychology, the sages and ascetics of India were led to explore the obscure zones of the unconscious. They had found that man’s physical, social, cultural, and religious conditionings were comparatively easy to delimit and hence to master. The great obstacles to the ascetic and contemplative life arose from the activity of the unconscious, from the samskāras and the vāsanās–“impregnations,” “residues,” “latencies”–that constitute what depth psychology calls the contents and structures of the unconscious. It is not, however, the pragmatic anticipation of modern psychological techniques that is valuable, it is its employment for the “deconditioning” of man. Because, for India, knowledge of the systems of “conditioning” could not be an end in itself. It was not knowing them that mattered, but mastering them, if the contents of the unconscious were worked upon, it was in order to “burn” them. We shall see by what methods Yoga conceives that it arrives at these surprising results. And it is primarily these results which are of interest to Western psychologists and philosophers.

[…]As we said earlier, the problem of the human condition–that is, the temporality and historicity of the human being–is at the very center of Western thought, and the same problem has occupied Indian philosophy from its beginnings. It is true that we do not there find the terms “history” and “historicity” in the senses that they bear in the West today, and that we very seldom find the term “temporality.” In fact, it was impossible that these concepts should be found under the particular designations of “history” and “historicity.” But what matters is not identity in philosophical terminology. It is enough if the problems are homologizable. Now, it has long been known that Indian thought accords considerable importance to the concept of māyā, which has been translated–and with good reason–as “illusion,” “cosmic illusion,” “mirage,” “magic,” “becoming,” “irreality,” and the life. But, looking more closely, we see that māyā is illusion because it does not participate in Being, because it is “becoming,” “temporality”–cosmic becoming, to be sure, but also historical becoming. It is possible, then, that India has not been unaware of the relation between illusion, temporality, and human suffering. […] What modern Western philosophy terms “being situated,” “being constituted by temporality and historicity,” has its counterpart, in Indian philosophy, in “existence in māyā.”

[…]To repeat, it is not a matter of purely and simply accepting one of the solutions proposed by India. A spiritual value is not acquired after the fashion of a making a new automobile. Above all, it is not a matter of philosophical syncretism […] still less of the detestable “spiritual” hybridism inaugurated by the Theosophical Society […] The problem is more serious. It is essential that we know and understand a thought that has held a place of the first importance in the history of universal spirituality. And it is essential that we know it now. For, on the one hand, it is from now on that, any cultural provincialism having been outstripped by the very course of history, we are forced […] to think in terms of universal history and to forge universal spiritual values.

[…]The conquest of absolute freedom, of perfect spontaneity, is the goal of all Indian philosophies and mystical techniques, but it is above all through Yoga, through one of the many forms of Yoga, that India has held that it can be assured. This is the chief reason we have thought it useful to write a comparatively full exposition of the theory and practices of Yoga, to recount the history of its forms, and to define its place in Indian spirituality as a whole.

–Mircea Eliade, Foreword to Yoga, Immortality and Freedom (1954) (Translated by Willard R. Trask)